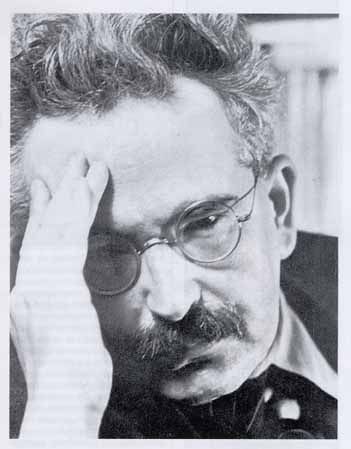

Going back to Johannes's recent post on the presentation of the Other (more specifically, relating to the marketing behind Ilya Kaminsky's first book, Dancing in Odessa), I have been struck by the obsession some American poets have for the German philosopher Walter Benjamin. Benjamin has been creeping into Jessica's comment field and in a recent post by Jon. Michael Dumanis has written a poem in the voice of Benjamin's in his last day (I have a copy of it somewhere) and Joshua Clover has an entire book inspired by Benjamin (Totality for Kids), going as far as paying homage to Benjamin in his author photo.

Going back to Johannes's recent post on the presentation of the Other (more specifically, relating to the marketing behind Ilya Kaminsky's first book, Dancing in Odessa), I have been struck by the obsession some American poets have for the German philosopher Walter Benjamin. Benjamin has been creeping into Jessica's comment field and in a recent post by Jon. Michael Dumanis has written a poem in the voice of Benjamin's in his last day (I have a copy of it somewhere) and Joshua Clover has an entire book inspired by Benjamin (Totality for Kids), going as far as paying homage to Benjamin in his author photo.While Jessica and Jon can be forgiven for actually discussion WB's work as a literary critic and his discourse on flânerie, I am a little bit more disturbed by the relative lack of references to his work in Michael's poem and in Clover's book, that is, beyond Passagenwerk. Sure, the comic absurd tone of Michael's poem points at Bertold Brecht's influence on Benjamin, but that tone is already present in Michael's other, non-Benjamin, poems.

There is an odd emphasis on Benjamin's biography, rather than his work, such as his attempt to combine the historical materialist aspect of Marxism with the transcendentalism of his Jewish upbringing or his significant volume Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit (I've just realized that I've been citing Benjamin's work in their German titles; this is not out of sheer snobbism, but rather because I've read those works in French and don't know the American translations). As I said, Michael's poem recounts how Benjamin fled the Nazi, trying to cross the border to Spain, thought that he and his friends had been denied access, lost his final manuscript (possibly the final draft to Passagenwerk) and committed suicide. Similarly, Clover pays homage to Benjamin's time in Paris, painting the city with stock images of the bucolic era of l'entre-guerre, although it seems at times that Clover is describing the Paris of the Belle Epoque. Cafés, belles filles, baguettes, you get the picture.

Benjamin's death was certainly absurd, but by focusing so much on his biography, don't we run the risk of eclipsing his work? We certainly find this problem in poets such as Plath, Berryman, Celan, Keats, Shelley and others. When are we going to find poems written in the voice of Louis Althusser, Bernard-Henri Lévy or George Canguilhem, people whose lives were not tragic or horrible?

More importantly, what purpose does this romanticization of the tragic Other serve? In a way, Benjamin "legitimizes" Michael's work in general by providing him a lineage and a philosophical background. But, beyond that, the American persona poem tends, as we have seen, to be in a tragic voice, and tends to take place in an idealized foreign place (and usually in the past). What does this nostalgia point at?

As for the intriguing number of persona poems in American poetry, I'll let Eric explore the topic.

Comments

I wasn't aware of the fascination with his life among contemporary avant gardes. That is interesting...

I find WB's work fascinating for more or less the same reasons, especially his heroic attempt to find a place for art within a Marxist framework.

I also failed to mention Bernstein's Shadowtime, which, unfortunately, I have not been able to acquire (Houston is very unkind toward the avant-garde).

Yes. Such as we neglect to see what a CRAZY person Benjamin was. "On Language as Such and the Language of Man"? Does anyone really BUY that shit?

Lorraine, yes you were aware, Charles just wrote an opera on him. (My hands are on my hips.) Remember?

Benjamin is GOD at Buffalo. I have his collected works, the Harvard hadbacks. now they're coming out in paperback and I feel like i got a raw deal.

I agree that Benjamin has some interesting concepts, but I think it's more useful to look at him as an artist than as a philosopher.

i wouldn't worry about translation, françois, i think people read enough fr & ger to figure it out. if they're, like, reading your post on benjamin. they should be able to.

Ha ha! Yes. But I I've been pondering the form and not the content. What's the deal with operas these days? Elieen Myles just had an opera (or operetta) of hers produced in New York last month called Hell.

I guess I'm still not really sure, either, what the difference is b/t the American Musical and the (European) Opera. This is probably criminal to say, but really, what is the difference?

I think the opera is a cool form. A few years ago I saw a musical? that my friend chelsea warren did some design for, and the whole thing was performed with huge human-sized puppets, and the set was crazy. it seems like there's so much potential in stage design. not to mention the potential whenever you start blending genres or looking for the "whole work."

now, for that matter, what is the difference between the american musical, european opera, chinese opera and noh?

Supposedly, content, from serious to comic in this order: Opera, opera comique, operetta, musical comedy. Musicals can be comic or no, but the singers don't have to be trained to sing in opera style. But this distinction doesn't hold, since opera stars have often performed in musicals on Broadway, etc.

Wagner wrote his own libretti. And then there was that Debussy opera based on Maeterlinck, right?

i was standing in line at the opera in vienna, which (city) is full of expats from various places who're studying opera. and i started talking to an american girl who had grown up staudying ballet and opera, and at some point in her late teens had had to choose which one to study "for real" because her ribcage was expanding from studying operatic singing. she couldn't "hold it in" anymore, since she was training to expand it... i'm not an expert, obviously, but when i was studying musical theater there was a lot of concentration on the stomach/diaphragm (sit-ups as part of training) for "belting." Where Operatic singing seems to maybe (maybe) be about producing sound from a voluminous body. which explains why musical theater singers can be teeny women and opera singers are very large. the larger your instrument, the better you can project sound... and so on.

yay, back to discussions of bodies!